A couple of weeks ago, I launched ClipSnag, a native macOS wrapper for a popular command-line tool called yt-dlp. The goal of this app is to provide the benefits of this wonderful tool to people who are not comfortable with a terminal or simply prefer GUI over command-line tools.

In this post, I would like to share the two things I learned while building this app:

Open-source doesn’t mean “do whatever you want”

The fact that software is open-sourced doesn’t mean you can do absolutely everything you want with it. Each open-source software is released under a specific license that describes how the software can be used, modified, and shared.

For example, the yt-dlp program is released under the “Unlicense license”. It’s a public domain equivalent license, which allows you to use, modify, distribute, or even sell the software without asking for permission or giving credit. This license would allow me to include yt-dlp as part of my own, paid app without any issues.

However, yt-dlp has several dependencies. All of them are optional, but two are highly recommended - ffmpeg and ffprobe, without which my app doesn’t work. They are used for merging video and audio files, converting between formats, as well as for various post-processing tasks. Most of their codebases are released under the “LGPL v2.1+” license. The license states that any “derivative” work must be distributed under the same or equivalent license terms. This effectively means that if I were to bundle ffmpeg and ffprobe executables within my app, I would have to make the app open-source as well and provide it under the same license.

Since open-sourcing the app wasn’t my intention, I had to find a different solution, and that solution would have to be aligned with the target audience for the app - potentially non-tech-savvy users. I wanted people to be able to download my app and start using it immediately without having to worry about downloading all of the necessary tools mentioned above manually. And how was I supposed to do that if I can’t include them as part of my app because of the license restrictions?

The exploration related to this question brought me to my second finding:

macOS allows apps to download and execute arbitrary executables

Firstly, let’s see what happens from the user’s perspective when they download an executable using their browser and try to run it.

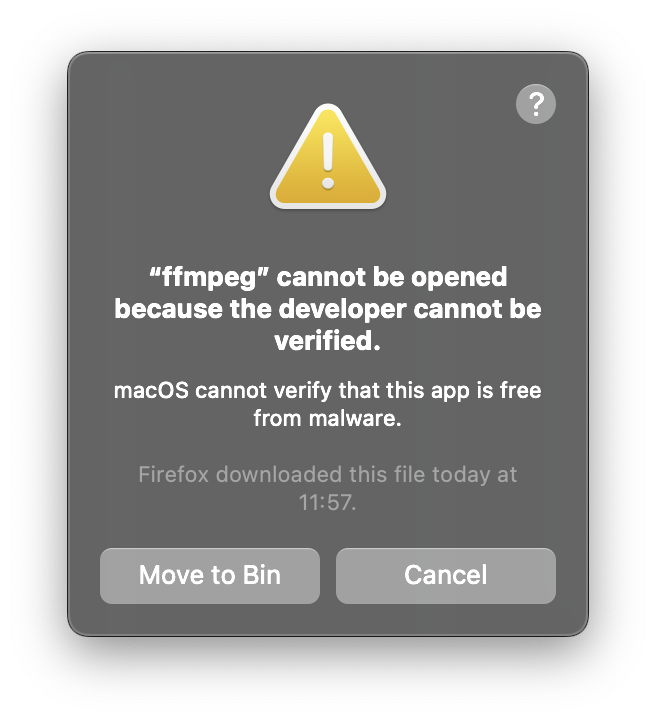

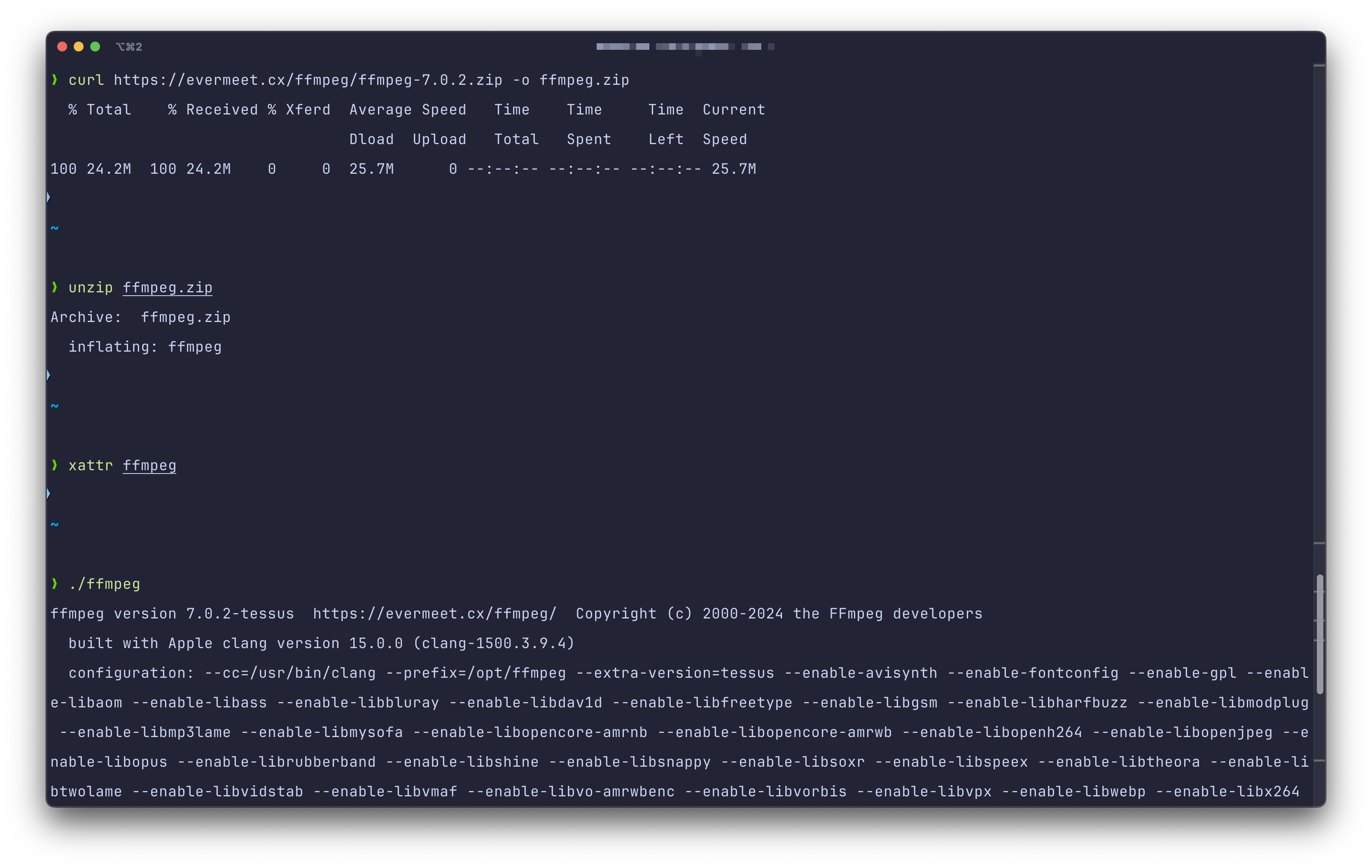

On my machine (running macOS Sonoma), this is what I got after I downloaded FFmpeg, unzipped it, and either opened it by double-clicking or typed ./ffmpeg in my terminal:

The reason for this alert is the Gatekeeper mechanism. By default, it verifies that any software you intend to run for the first time is from an identified developer, is notarised by Apple to be free of known malicious content (since macOS Catalina), and hasn’t been altered.

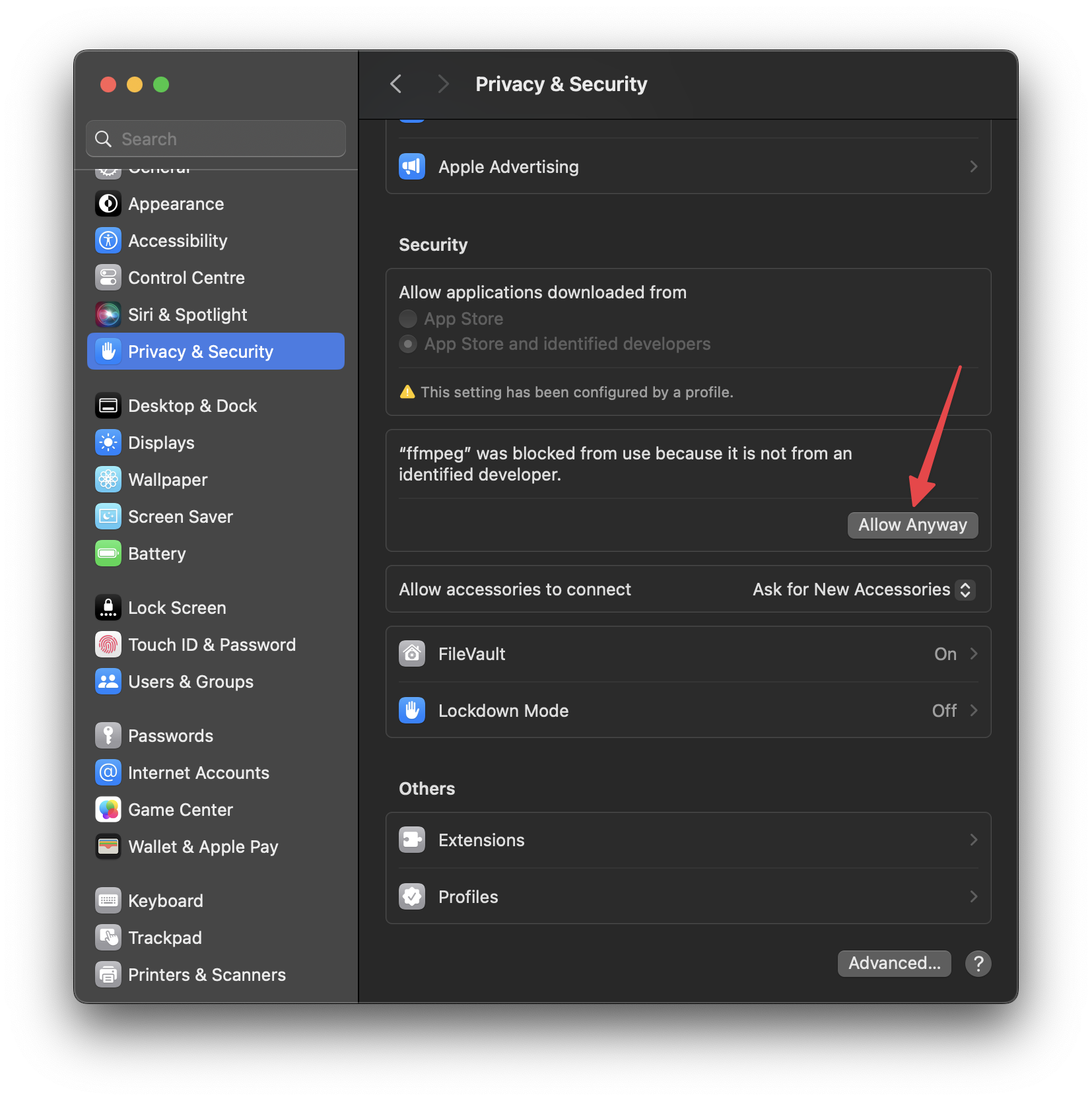

In this case, the ffmpeg binary isn’t signed by a certified Apple Developer hence the warning that “the developer cannot be verified”. One way to work around this is to open System Settings, go to the “Privacy & Security” tab, and click on “Allow Anyway” in the section mentioning ffmpeg:

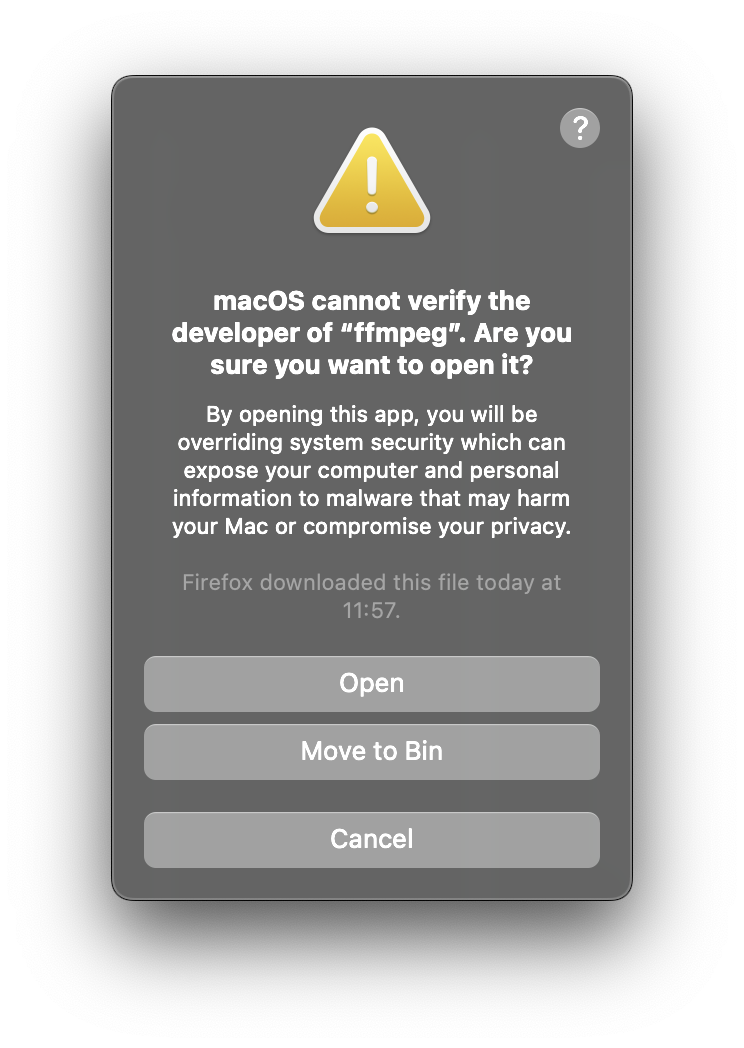

Then we can run the program again and confirm the will to open:

As you can see, a lot of steps are required - downloading the archive, unzipping it, running the executable, clicking “Allow Anyway” in the settings, running again, and finally, confirming. Given that my app requires three external dependencies, which can’t be bundled because of the license restrictions, the above steps would have to be performed three times, manually.

I considered preparing a detailed instruction for a manual installation of all of these tools for my users, but that would be way too much to ask from them, especially given that the app is paid. It should run out of the box, without any additional work.

This almost led me to abandon the app altogether, but then I realized that none of the above steps are necessary when downloading an executable using a non-browser tool, like curl or a simple Python script.

Why is that?

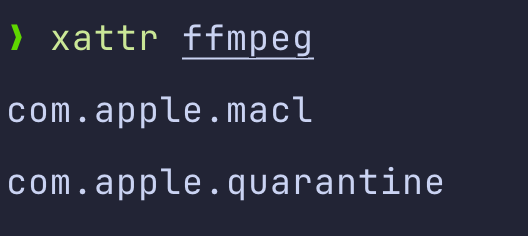

Firstly, it turns out that what triggers all of the Gatekeeper checks is the com.apple.quarantine extended attribute that is attached to all downloaded files.

If we run the xattr program (that’s used to work with extended attributes) on the downloaded ffmpeg executable, we can see that indeed, this attribute is present:

Secondly, Gatekeeper will only verify applications that have the quarantine flag. The problem is that this flag is added by other applications, not by the operating system itself. It’s the responsibility of app developers to make sure that this flag is added to any files downloaded by the app.

Apps like web browsers or email clients properly attach the quarantine flag to all downloaded files, but many don’t, like most BitTorrent client software. The flag is also not added if the app came from a different source, like network shares or USB drives.

To illustrate this, let’s download ffmpeg again, this time using curl. Then, when we unzip it and run xattr on the executable, we can see that there is no quarantine flag attached. Also, running doesn’t trigger any OS alerts:

We bypassed all Gatekeeper checks by simply using a program that doesn’t attach the quarantine flag (that’s one of the reasons why this mechanism received some criticism).

I used the exact same “trick” in my app. Instead of bundling yt-dlp, ffmpeg, and ffprobe within my app, which would violate their licenses, or requiring users to download them manually, I simply download the dependencies upon the first app launch and store them outside of the app in the user’s home directory, without disrespecting the licenses.

Problem solved!

One final, but very important, thing to note is that the above little experiment proves that it’s always crucial to make sure that we only open apps we trust. On the surface, the Gatekeeper mechanism sounds great and you would think it fully protects your computer against running potentially malicious executables, but, as we’ve seen, that’s unfortunately not always the case.