Introduction

In this post, I would like to write about an interesting concept I learned while reading Designing Data-Intensive Applications by Martin Kleppmann. More specifically, it’s a story of how Twitter handled some of its scalability challenges related to users’ personalized timelines. If you work on an application with some sort of a personalized feed/timeline for each user, the idea introduced here might help you improve the performance or give you inspiration for your next app’s architecture.

Scaling timelines

In November 2012, at a conference in San Francisco, Raffi Krikorian published some data about two of Twitter’s main operations:

- Post tweet - a user can post a new tweet to their followers (4,6k requests/sec on average, over 12k requests/sec at peak).

- Home timeline - a user can view tweets posted by the people they follow (300k requests/sec).

With modern databases, handling 12,000 write requests is achievable fairly easily. But at Twitter, the challenge came not with the volume, but due to so-called fan-out. In transaction processing systems, this term is used to describe the number of requests to other services that need to be made to serve one incoming request. On Twitter, each user follows many people and each user is followed by many people. This means that when a new tweet is published, it needs to be delivered to all of the author’s followers. In some cases (e.g. celebrities with many followers), there might be a lot of work to do.

On a high level, there are two ways of implementing the two operations mentioned above. Let’s examine both of them.

Traditional approach with relational schema

This is probably the first approach that comes to most developers’ minds. The idea is relatively simple. We need some kind of storage for all posted tweets. When a new tweet is posted, it’s simply inserted into this global collection of tweets. When a user opens the website and requests their home timeline, all the tweets from all the people they follow are merged and served on demand. In a traditional relational database, you might have three tables to handle this scenario: users, tweets, and follows.

- users table

| id | first_name | last_name | username |

|---|---|---|---|

| 21 | Arkadiusz | Chmura | ClouddJr |

- tweets table

| id | user_id | content | created_at |

|---|---|---|---|

| 14 | 21 | Hello World! | 2022-03-26 17:46:11 |

- follows table

| follower_id | followee_id |

|---|---|

| 19212 | 21 |

Then, to get all the relevant tweets to assemble a user’s timeline, the SQL query could look like this:

SELECT

tweets.*,

users.*

FROM

tweets

JOIN users ON tweets.user_id = users.id

JOIN follows ON follows.followee_id = users.id

WHERE

follows.follower_id = CURRENT_USER

The biggest problem here is that we have to execute the above query every time we want to display a timeline for any user. It’s not hard to imagine the huge amount of work required when there are a lot of users on the platform with a substantial number of people they follow frequently accessing the website.

The first version of Twitter used this approach, but the system struggled to keep up with the load of home timeline queries. The number of users on the platform kept growing, so they had to introduce another solution.

Maintaining a cache for individual timelines

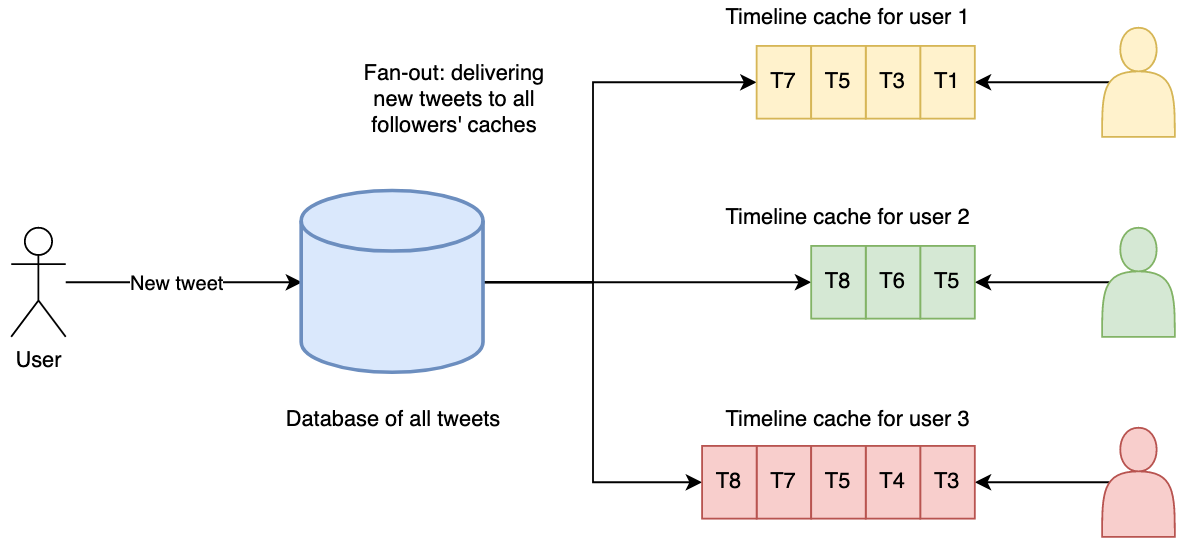

Here, the basic idea is that we prepare, or cache, each user’s home timeline ahead of time so that when it’s requested, no additional work is required. When a user posts a tweet, besides being stored in a table, it’s immediately inserted into timeline caches for all of their followers. Thanks to this, reading a timeline is very cheap, because it has already been computed - it’s enough to just read from the cache. There is no need for any other expensive database operations. This concept is visualized in the image below.

Twitter’s data pipeline for delivering tweets to followers (2012)

When it comes to actual tools that you could use to implement the timeline caching mechanism, a great option would be a very popular, open-source, in-memory data store called Redis.

However, while reading all relevant tweets for each user is very cheap right now, there is one downside of this approach. Posting a tweet now requires a lot of additional work. Besides storing it in a table, it has to be inserted into many other caches. The average number of followers per user is 75, which means 4,6k new tweets per second becomes 345k writes per second to the home timeline caches (4,6k * 75).

But the average is affected mainly by users with many followers (there are some with more than 30 million). The majority of users have much fewer followers. This means that the extra work required for the fan-out when posting a new tweet is only noticeable for that small number of users with a very large number of followers.

For this reason, Twitter moved to a hybrid approach to take the best of both worlds. Tweets from “regular” users continue to be fanned-out to timeline caches, as illustrated above, while tweets from celebrities are excepted from that process. When a home timeline is requested, tweets from celebrities are fetched separately from the database and merged with what’s inside the user’s cache.

Summary

If you found this story interesting, you might enjoy reading the book it was mentioned in - Designing Data-Intensive Applications. It’s a good combination of the theory behind many enterprise-level tools and practical engineering. It compares many tools and approaches, including their strengths and weaknesses, to make it easier for us to decide what’s best for our applications.